In the Elementary series I discuss various game design approaches and figuring out what makes them tick, how to improve them, and brainstorm game design. This one is dedicated to Horror-style games.

My recent review of Resident Evil 7 opened an opportunity for me to discuss the difference between effective and ineffective horror game design. This article won’t be a commentary on RE7 specifically, but we’ll use that game to help inform our discussion. I’ll be using some principles of design and terminology introduced in my Revisiting Game Genres article, so you may want to read it.

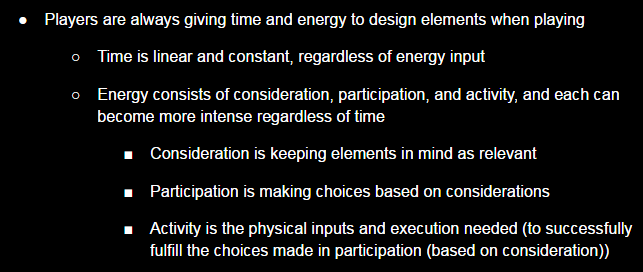

Let’s start with a very basic concept of the time-energy investment principle:

Understanding horror intensity

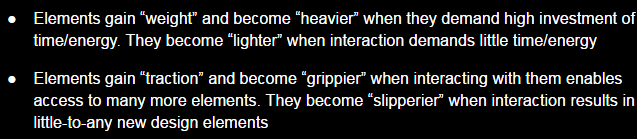

In Horror, we want to demand the player’s energy almost constantly, but not through Activity. The best horror is in the realm of the mind, so that’s where we want to challenge players the most. Thankfully, the instinct to survive comes naturally in a video game where you embody a person, so it’s easy to exploit this instinct by introducing more factors relevant to survival. More factors means more investment of Consideration (one of the forms of mental energy) if players want to survive. In Resident Evil 7, the highest investment of Consideration is asked of us when we know (or suspect) that Jack (a Coercive game element that does not wait for us to voluntarily interact) is somewhere in the house waiting to show up and kill us. If we’re playing for the very first time and have no idea what to expect from him, every minute feels like a countdown to another awful fight. Our mind wants to prepare for that possibility, and we’ll quickly begin formulating how to optimize our chances. The game establishes that he’s an incredibly resilient enemy who always has a deadly weapon with him, so the room for error is small when dealing with him. Let’s quickly run down the factors we must keep in mind due to his specific design elements: (1) awareness of whether he’s anywhere nearby; (2) awareness of entrances he might suddenly show up through (including busting through walls, floors, ceilings, etc); (3) awareness of every viable path you could use to escape with if he shows up from any of these points; (4) awareness of hiding spots; (5) current weapons/ammunition to fight with if you have no other choice; (6) current health/healing items; (7) knowledge of where to find additional items if the situation demands it. That’s already a lot to think about, but it could easily be expanded if we added more factors. The fact that he’s an obstacle and not the objective itself means we have to keep moving around and focusing on other challenges while he weighs on our mind.

The situational awareness factors alone are enough to create a stressful and engaging horror experience because of our limited awareness. The inherent gameplay elements of using first person perspective and having slow movement creates a steady weight that multiplies whenever we hear noises that we think indicate something important. Because we can’t see all around us, we don’t want to let our guard down even if we think we’re safe. Creating a plan around the possibility of meeting Jack automatically converts every nook and cranny around us into pieces of a survival puzzle that we might need to solve at a moment’s notice. Nobody is helping us or giving us advice along the way, so our brain has to work overtime to guess at what the best course of action is. There are no checkpoints, way markers, or clues about the “correct” solution. The player is given plenty of reliable information about themselves, but not about the surroundings or the enemy. For all we know, we are making foolish choices every time we turn the corner. This is where Consideration becomes Participation. Even if nothing is happening, we still feel like we need to make important decisions in the event that Jack does show up. Plan A, B, and C are being sketched and adjusted. Jack’s ability to adapt and exploit his surroundings means it’s not even good enough to simply keep one effective strategy in mind — we also need to rapidly evaluate what he might do in every situation if he shows up.

Executing our plans (Activity) shouldn’t be simple or easy necessarily, but the strain of inputs shouldn’t be high in general, because otherwise we won’t be able to devote proper mental energy to Consideration and Participation. As a general rule of thumb, only two of the three types of energy should be greatly demanded at a time. Menus, movement, interaction, and other basic controls should be intuitive and easy for this reason. In turn-based games, where time is generous and Activity requires no skill, the breadth of choices and the depth of their implications can be multiplied. X-COM (a horror game in a sense) builds intensity by forcing players to calculate hundreds of factors every turn, managing resources of life, Action Points, ammunition, visibility, etc. with the utmost care. In real-time games like Resident Evil 7, the exact mechanics of how pausing the game even works needs to be considered carefully. This is why the choice to keep the game happening while you arrange your inventory is a nice touch. Inventory management thus becomes a skill you can fail at, if you are clumsy, indecisive, or use it at the wrong time. Checking your map, on the other hand, does pause the game, which feels fair because your character would probably remember layouts and objectives even though you as a player might forget.

The role of safety

As with any emotion, horror needs to be allowed to rise and fall if it’s to remain effective. Safety is what players will constantly search for when they feel threatened, and yet ironically, relieving stress and enjoying that safety will only serve to recharge our fear batteries. The moment we leave safety is the moment we refresh our memories and sink back into survival mode, now with renewed focus and a chance to second-guess what we did last time. Players can only invest so much energy into a game before they burn out and quit, so safety must be available. It can be as minor as partial protection from danger (cover to hide behind, or easy access to a doorway we can shut behind us) but it can also be as blatant as playing soothing music and giving us a chance to save our progress. It might seem strange, but experiencing long stretches of safety can both amplify our sense of anticipation, and tempt us into relaxing (which would be a reduction of Consideration and Participation). A series of non-threatening hallways where everything seems normal and safe can therefore have the opposite effect, as we push our imagination to the limits to figure out where the threat will be coming from. Horror is all about preparing for the inevitable, not running around in a panic constantly.

Assurance is another form of safety. The more players know about the situation, the fewer possibilities they have to account for, reducing the load on their mental energy. Guessing is hard work. Our chances of success go up when we can strategize around solid facts. You’ll find that playing Resident Evil 7 a second time is hardly scary at all because we know what to expect and how to deal with things. X-COM, on the other hand, remains quite intense no matter how many times you’ve played because the maps and the exact details of what’s inside them are randomly generated. When possible, finding facts (or “intel”) becomes an important element of survival and safety. As designers we can leverage this.

Besides intense gameplay stakes, the music and atmosphere inspires fear. The bottom of the four meters shown on screen is a “Morale” meter that visualizes how close your soldier is to losing their mind. Psychic attacks can directly target this, and only experience in missions can increase it.

UPDATE: Here’s something Hideo Kojima recently said regarding Horror games…

He says that the “unknown” is very scary, but the idea of seeing things “slightly out of the ordinary” is the most effective approach because it adds “confusion”. This perfectly matches what I’m saying, because confusion and being forced to guess about things are strong methods of demanding Consideration and Participation from players. The reason I’m placing this quote in our role of safety section is because feeling safe — thinking that things are “ordinary” — and then suddenly noticing that something is disturbing/wrong/threatening forces players to very rapidly shift gears and compensate for letting their guard down. They will also stop trusting anything they see, no matter how ordinary it may seem. Establishing reasons to be paranoid is important, and Kojima’s method does exactly that.

Earning every bit

When you want to add weight to an experience, ensure that the time/energy investment is enough to create a sense of relief when you finally accomplish things.

In Resident Evil 7, most interaction is light, which allows players to race through the game if they know exactly what to do. Information gathering and searching for potentially useful elements are the heaviest things you spend time/energy on, and you’ll only need to do this on your first playthrough. This makes their choice of on-screen prompts — communicating nearby interactivity — an extremely buoyant element that removes the weight of searching. It takes away the guesswork and allows us to shut off part of our brain. Instead of having prompts, imagine if hundreds of useless objects in the house could be examined, manipulated, and searched as potential clues. The whole house would feel different. Some games (Bethesda’s large RPGs and the Ultima series come to mind,) approach this level of interactivity, but with less purpose, and obviously with less impressive graphics. Now imagine if those items were arranged randomly at the start of the game so you couldn’t memorize them; players might spend hours just rummaging around a room for some small trinket they think is nearby, or evaluate each object for potential clues or uses. Would that be too much investment for too little gain? Perhaps. But as it stands, we can almost robotically slide along walls and shelves tapping the interaction button whenever we see a prompt and not have to think about much at all. Also, we could introduce elements that help us narrow down our search radius and thus make sifting through piles of garbage a punishment for players who don’t find the clues.

Foreshadowing and teasing the upcoming game elements (even if they’re negative ones) is a powerful incentive because players will automatically work towards new experiences once they find out about them. As players, we want to experience the whole game and get our money’s worth. We are literally paying money for the ability to earn things through time/energy investment. Prospects in Horror games always include a balance of good and bad, creating an ambivalence about progress. Obtaining something good usually indicates that something bad is going to happen, but bad things are also usually connected with rewards. This correlation shouldn’t be too strong, lest they take the difficulty curve of the game for granted and thus feel comfortable. When you’re initially confronted by Jack in RE7, it’s obvious that you’re way outmatched, setting the tone early that the game won’t hold back. As you get deeper into the game, the correlation between helpful elements and harmful ones becomes almost exact, thus ruining the tension. The game actually concludes much less scary and challenging than it begins.

Scattering “ancient coins” throughout the game at illogical points and then having them serve as currency for unlocking upgrades is a perplexing example of awful incentive elements. Initially we have no idea what they’re good for, so we feel silly that Ethan would collect them for no apparent reason. We are forced to wonder why he’s willing to collect these apparently useless coins instead of picking up more practical things we notice laying around such as kitchen cutlery, shovels, and blunt objects. The logic of the situation does not call for coin collecting, so this already undermines our immersion. Even once we realize that the bird cages use the coins for some reason, we have no idea how frequent the coins will become from that point on, or how many we may have already missed. Should we go back and search for them? Will we start getting them at regular intervals and end up with more than we need? When will we find other bird cages, which may have even better upgrades? None of these are addressed, even though the owner of the bird cages — Zoe — is a contact of ours. The message we get from the game designer is therefore clear: scour every square inch of the game for tiny hidden coins if you want the best toys we’ve designed, and logic be damned. They took the time to craft a detailed-looking world, and they insist you spend time looking at it all even if they have to bribe you.

It should be noted that although RE7 does practically nothing with its characters (in terms of non-combat interaction), relationships are one of the most robust and elegant ways to control time/energy investment in game design. The more we put into a relationship with a character, the more we can reasonably expect to get back. This is one of the principles of “Game Theory” itself as a social phenomenon. Finding out more about characters through conversation, separate research, etc. is therefore a worthwhile investment if we can gain their trust and cooperation. In a horror game, the potential for negative interactions (such as being abandoned, attacked, betrayed, lied to, coerced, etc.) might be even more effective in terms of motivating us, causing us to develop a relationship just to mitigate the risk to ourselves if things go wrong. “Story-driven games” rarely treat characters as investments and allow for branching possibilities, however.